Shards Of Consciousness

Maintaining focus in the 21st century

My mind is in at least twenty different places at any given time of day. Between work, personal, and domestic obligations, I feel like I’m always mentally ping-ponging back and forth between various sets of tasks I need to complete or consider.

Has adult life always been like this? I don’t recall my parents being this stressed when I was younger, although maybe they did a good job of hiding it from me. I was also very lucky in that my dad worked and my mom stayed home and took care of the house. Their roles and responsibilities were clearly delineated. But now, because it’s almost impossible for a family to live comfortably on a single income, both parents are forced to take on work and domestic duties. Instead of playing one role well, they’re forced to play all roles to varying degrees of success.

But that feels like an economic problem, not necessarily a technological one. What is it about modern technology that is making people, myself included, feel so chaotic and disunified?

My deepest apologies for the cringe Elder Millennial reference here, but the best metaphor I can think of comes from Harry Potter. In order to cheat death, Voldemort puts pieces of his soul into seven different totems, called Horcruxes. The plan works, although it has the unfortunate side effect of turning him from a man into a demonic villain that resembles a salted slug. He’s alive, sure, if you can even call his state of being “living.” But he’s completely out of harmony and focused only on acquiring power and crushing his enemies. By breaking his soul into pieces, he has survived physically, but destroyed himself spiritually.

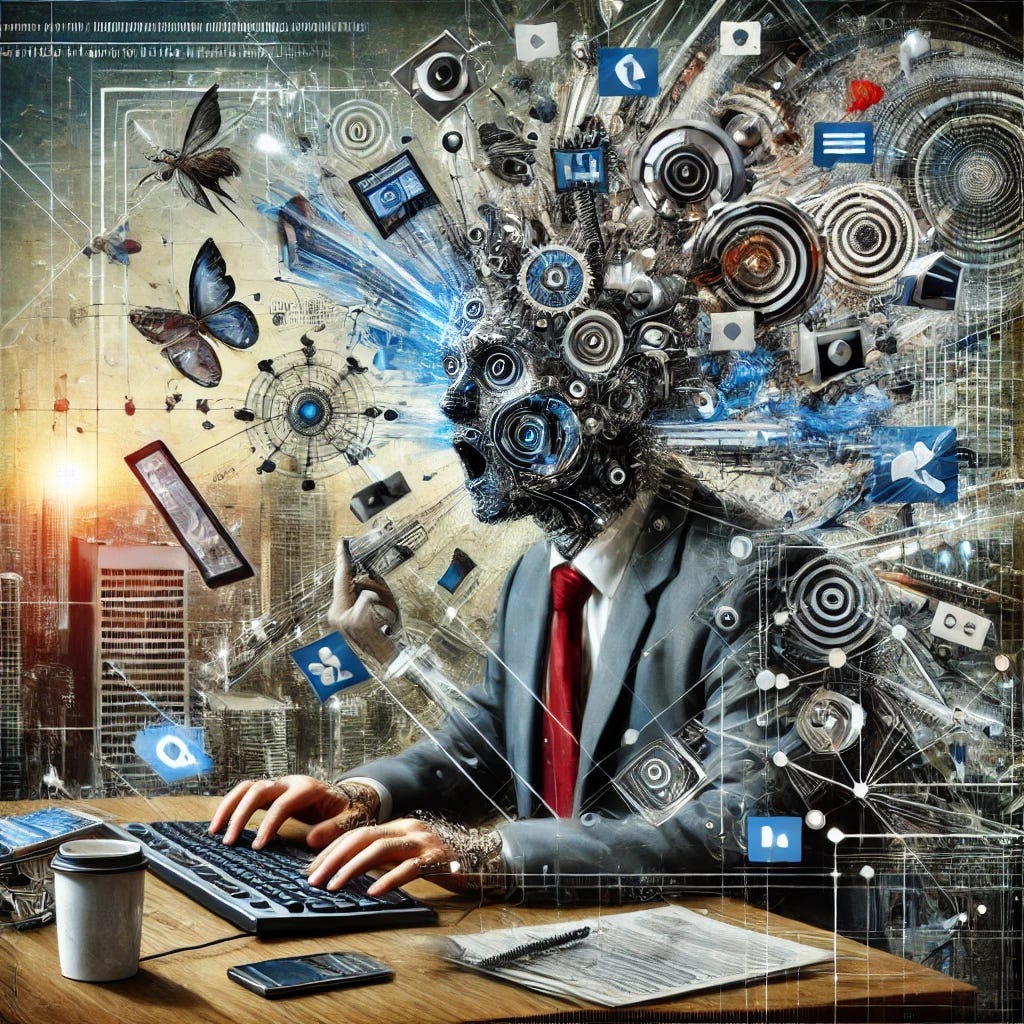

Another major apology for how overdramatic this sounds, but I think this is what smartphones are doing to us. I’m not joking. Every app, every notification, every message, every TikTok is a mini Horcrux where we store a piece of our consciousness. The more pieces we give away, the more fractured we become. How can we expect to feel content and full when our spirit is scattered across the Cloud?

I know this all sounds ethereal and kind of woo-woo. Let’s get grounded and practical. Think about all of the points of contact we encounter in our day to day lives as typical, working American adults. We wake up, greeted by whatever notifications have accumulated overnight (Text messages, emails, etc). Maybe we check social media. We catch up on memes, the news, and the goings on of celebrities and our friends. Already, before getting out of bed, we’ve ingested more information than a typical American took in during any given month 100 years ago.

But it doesn’t stop there.

We get to work and the hits keep coming. We take in Slacks, meeting invites, and professional emails, which differ in tone and required levels of focus than the personal emails we looked at earlier in bed. Efficiency tools have allowed us to work faster, but instead of simplifying our workload, they’ve paradoxically increased it. We’re hit with more data and information than ever before, and as a result we have to make more decisions, weighed against more variables and outside factors, than any working person ever has.

On top of these work responsibilities, we continue to receive personal communication from friends, family, and corporations throughout the day. Group chats to keep up with. Funny tweets to respond to. Instagram stories to watch and like. Promotional emails to capitalize on. It never ends, and that’s the point. It’s literally designed not to end, for us to keep going, forever.

I say all of that to say this. Every single one of these interactions, personal and professional, takes up space in our brain. Even if it’s happening subconsciously, we give them thought and decide how to sort them. They require something, and take something, from us. Focus is not an infinite resource. There’s only so much we can give, to a certain amount of topics, during the day.

Because we receive so many data points on a daily basis, and because these interactions are all so disparate and disunified (I tried in vain to find a clip of a podcast I once heard where Bo Burnham discussed the true absurdity of social media: that within three swipes you’ll see posts from Wendy’s, your mom, and the President, and the fact that these all exist on the same platform is disorienting in a way that we’ve yet to fully comprehend. It’s the best articulation of this phenomena that I’ve ever come across), they in turn make our waking lives disparate and disunified.

Compare that to a working person in the 70s or 80s. What was their day to day life like? They woke up, maybe read the paper or turned on the morning news. That information went one way. They were not in control and did not have any personal relationship to what they saw.

After that, they would get in the car and listen to the radio on the way to work. Maybe they had a selection of a few cassettes they could pop into the tape deck. Either way, the options were extremely limited.

What did they do once they got to work? Most office workers didn’t have computers or email. They certainly didn’t have Slack or Zoom. All they really had were face to face interactions with coworkers, or the phone. If they were in a really fancy office they might have had a fax machine, but that’s it.

Afterwards, they’d go home, have dinner and maybe watch some TV before calling it a night. The next day would likely bring more of the same.

Think about what a different existence that was. Try to actually sit and imagine all of the moments of quiet, of dead space, of nothingness, that existed in a life such as that. All of that space has now been filled in by modern tech and communication.

So this ultimately begs the question, what can be done about this? The unfortunate answer is “Not much.” This tech is too ingrained in our lives, both personal and professional, to ever fully solve the problem. There can only be small, temporary solutions instituted at the individual level.

I’ve had to start physically separating myself from my phone throughout the day. When I get home from work, I keep it in another room so I don’t feel tempted to thoughtlessly pick it up for no reason. There’s no surer sign that you have a problem with your tech than when you pick up your phone, only to realize you can’t remember the reason that you picked it up in the first place. Creating physical distance between yourself and your phone solves this problem.

I’ve also started putting my phone in my desk drawer when I’m at the office. That way I’m only focused on work stuff, which makes it easier to get my tasks done. Knocking out a twenty slide PowerPoint is borderline impossible when TikTok is an arm’s length away.

Most importantly, I try to delay looking at my phone for as long as possible in the morning. Luckily, it’s already in another room when I wake up, so I don’t have an opportunity to look at it before I get out of bed. But I try and see how long I can make it once I’m up and moving. I’ve noticed a correlation between the amount of time I go without looking first thing in the morning, and how tempted I am to look later in the afternoon. It really does help to start the day off on the right foot.

I’m sure you’ve been offered solutions like this plenty of times before. I wrote about something similar in one of my first posts. But just because you’ve already heard them doesn’t mean they don’t work. Sometimes it takes awhile for a good habit or idea to sink in. You just need repetition to hammer the point home. And yes, this doesn’t solve the problem of the overall volume of data points you get during the day, but I find periodic bursts of information easier to manage and less psychically disturbing than the steady drip drip drip of constantly checking my phone all day long. With physical time away from my phone, I have the space to discover those moments of quiet that were much more frequent in earlier decades. This helps reduce my overall mental fatigue.

I’m currently reading Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media based on a recommendation from Luke Burgis’s “Anti-Mimetic Reading List.” Before I sat down to write this piece, I happened to come across this passage in the book:

“In the same year, 1844, that men were playing chess and lotteries on the first American telegraph, Soren Kierkegaard published The Concept of Dread. The Age of Anxiety had begun. For with the telegraph, man had initiated that outering or extension of his central nervous system that is now approaching an extension of consciousness with satellite broadcasting. To put one’s nerves outside, and one’s physical organs inside the nervous system, or the brain, is to initiate a situation - if not a concept - of dread.”

Whether we’re talking about the telegraph, as McLuhan was here in 1964, or iMessage, the effect is the same. We’re extending our nervous system outside of ourselves. All we can do at this point is, with great care and intention, sever that outer connection during times when it does not benefit us. It’s not easy, but it is simple. You just have to wake up every day and decide to do it, preferably before you pick up your phone.